Scroll to the bottom of this post to see a video of me on stage.

Sarah Lacy has been the subject of a lot of SXSW and blogosphere abuse for her poorly planned and executed interview with Mark Zuckerberg, CEO of Facebook. Whether or not that’s true, when you’re up there live dealing with an on stage disaster, playing the “Could’ve, Should’ve, Would’ve” game is not going to get you out of that jam.

I used to work as a stand up comic and suffered many many rough crowds. When I performed I had to deal with a whole variety of obstacles:

I used to work as a stand up comic and suffered many many rough crowds. When I performed I had to deal with a whole variety of obstacles:

- I’ve had your run-of-the-mill hecklers.

- I’ve had the music turned up on me in order to shut me up and get me off stage.

- I’ve had a single jackass clapping slowly, loudly, and sarcastically.

- I’ve had to perform in a DJ booth ten feet above and fifteen feet away from the audience.

- I’ve had a guy rushing the stage.

- I’ve even had beer thrown at me.

While I wasn’t at SXSW to witness the debacle, I’m offering Sarah Lacy and all of you some road-tested advice on how to deal with unruly crowds.

Lacy got to perform in front of a sober audience. She faced a bunch of nerds yelling at her to ask tougher questions. That sounds like a bubble bath compared to what road comics have to deal with. While I had tougher nights than Sarah Lacy, I didn’t have the blogosphere and video replays exposing my every flaw to the world. Nor did I have to suffer through every two-bit critic’s endless post-game analysis. For that I’m grateful.

If you ever find yourself in a similar situation here’s some advice on how to deal with a rough crowd.

ALWAYS stay in charge

I don’t care if you haven’t gotten a single reaction (or laugh) from the audience. Always stay in charge. Do NOT let the audience take over. If you do, you have no right to be on stage. So much of performing has to do with stage presence and making the audience feel that you deserve to be on stage. On stage confidence actually puts the audience at ease. If they don’t feel that you’re in charge, it makes them nervous and uncomfortable. Much of that feeling has to do with the way you walk out on stage and greet the audience. Here’s a simple trick:

When you walk on stage, greet people to your discussion. It’s YOUR hour of conversation. It’s not something you were booked to do. You OWN the hour and your guest is someone YOU invited.

In Boston, the comedians used to book their own shows. Headlining comedians would host showcase shows of six to eight comedians. They always made it very clear to the audience throughout the show that the other comics were friends of theirs and you the audience were invited guests to their party. They made the show their own.

Tell a personal anecdote that connects you with the guest

If things are going really south, bribe the audience with a personal story about you and the guest. Say something like, “I wasn’t going to talk about this, but my guest and I have a history together…” Break out a personal story. Make it human, and real. Drop any facade you may have put up until this point. The audience will appreciate it. It could even be something that just happened minutes before you walked on stage. But better yet is if you can tell a story of your past history together. This will calm the audience and explain to them why you deserve to be on the stage. Your moderating is not a fluke.

Look DIRECTLY at the audience

There’s a tendency to move your head or look above the audience. Don’t do that. There is a monumental difference when you consciously make eye contact with members of the audience. Look directly at people as you’re speaking. People will sense nervousness and evasiveness if your eyes keep darting and you don’t look directly at them. Also, it’s hard for people to be angry if you make direct eye contact with them.

You can actually see this difference with video email. Rookie video email senders end up looking down at the video of themselves on the monitor as they’re recording. This results in a lack of eye contact. Don’t look at yourself, look at the camera and make eye contact. Eye contact tells your audience you want to talk to THEM.

The big debate: Should you or shouldn’t you acknowledge what’s happening?

There are definitely two schools of thought here. And here are the arguments for the two sides.

Acknowledging what’s going on will get you out of a jam very quickly. Comedians have what is known as “save” lines. These are either self-deprecating or audience-insulting lines that acknowledge that things aren’t going so well. Lines like: “Is this an audience or an oil painting?” “Did I mention I have videotape of ALL these jokes working?” “Was there an ether leak in here?” “I’ve got a brand new handgun, and I can’t wait to get home and use it.” (These lines are a combination of my own, one is from Lord Carrett, and the first is older than Abraham.)

Not acknowledging what’s going on and plowing on with your interview/performance will gain far more respect from the audience IF you can pull it off. That’s a BIG IF.

When I was a young green comedian, I would bail with “save” lines the second I sensed things going south. The reason I did this is you can get quick laughs with a “save” line because the audience thinks, “Phew, he knows this isn’t going well, and he’s OK with it. He’s telling us so.” The problem is “save” lines don’t build any respect with your audience. I know I’m going to get a lot of flack with some of my comedian friends who make “save” lines a core part of their act, but I don’t think it’s a good idea if you want to build audience respect. If you’re confident with what you’re doing, keep plowing ahead with the intent of winning the audience back the good ‘ole fashion way–with your talent.

I remember performing in a very noisy music nightclub in between musical acts with a comedian friend of mine, Derrick Leonard. Derrick was a great comic (he stopped performing like me). That night the audience was unruly. When I performed, I pulled a billion “save” lines (I was very green), but when Derrick performed, he just maintained focus and continued on with his act. Eventually, after about five minutes the audience finally came around to Derrick and he won them over. When you walk off stage, that’s definitely the way you want to be perceived.

Still, I understand the tendency to acknowledge what’s going on with a “save” line. It will get you out of an immediate jam and breathe a sense of relief across the whole room. But it doesn’t build your brand in the long run.

Get quieter

This is a little known trick made popular by comedian Robert Schimmel. When the audience gets loud, there’s a tendency to try to shout over them and feel that you’re going to win because you’ve got a mike and an amplification device. This doesn’t work unless you are by nature a very loud performer. Even then, you’re playing an extremely dangerous game. You better have some winning bits up your sleeve to succeed at the yelling game.

Instead of yelling, do what Schimmel does and get unbelievably quiet. When you start talking very quietly the audience will quiet down to hear what you have to say. It works, but for it to work, you have to commit to it. Keep doing it and the audience will eventually quiet down. They want to hear what you’re saying.

Don’t ask the audience to quiet down

Nothing screams, “I have no control over the audience” than saying to them, “Hey guys, shut up.” Again, like the “save” line, it’s the impulse reaction. Instead of asking for quiet, pause for a very long time-an uncomfortably long time, look at the audience, and then continue on. Try the quiet trick too if you like.

Talk to one member of the audience as if they’re representing everyone

While I suggest in some occasions that you should not acknowledge what’s going on, that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t talk to the audience. Pick one person in front who isn’t causing a ruckus and ask them if they have a burning question they’d like to ask. Get personal with them. Ask what they do for a living. Ask them what they hope to get out of the talk. If they haven’t gotten what they were looking for, now you know what the next line of questioning should be. Start asking those questions and then go back to that person. Ask him/her, “Did we answer your question? Anything more?”

That’s my advice from my former comedian’s perspective. When I moved into tech journalism I attended many industry conferences and participated in or witnessed many panel discussions. I truly believe that a poor panel is the moderator’s fault, and after witnessing so many poor panel discussions I wrote an article entitled “More Schmooze, Less Snooze: How to Deliver ‘The Most Talked About’ Conference Session.” It’s got advice for moderators, panelists, and even attendees.

Read it now before you become the next Sarah Lacy story.

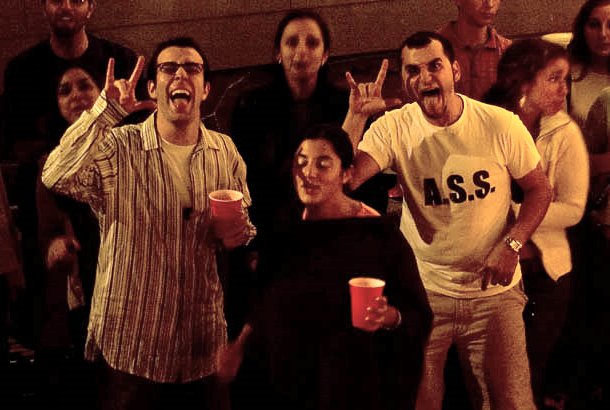

And here’s me from my stand up days.

Photo credit: Creative Commons SeanSantry